As you might know, I wrote an article on how to deal with time pressure in chess. What I didn’t cover in that article came back to haunt me in the recently concluded Sharjah Masters 2025.

The problem I’m referring to is playing impulsively — moving too fast at critical moments. There’s a difference between playing fast and playing too fast. Playing fast is fine as long as you’re emotionally in control and consciously processing the position. This particular problem affects not only players who play too fast, but also those who frequently find themselves in time trouble. At some point in the game, we all tend to make moves a bit too quickly.

Even a non-chess player can understand the drawback of moving too quickly: you’re more likely to make a mistake because you haven’t fully evaluated the position.

What I want to talk about in this article is a common habit among chess players — responding instantly as soon as the opponent makes a move. There are different reasons we fall into this pattern:

- To show confidence or assert dominance

- To gain time on the clock

- To reach the next time control faster

- Believing it’s an obvious or automatic move

In this article, I’ll share some impulsive mistakes I made during a recent game, along with the thought process behind each move.

The game was played as black against Grandmaster Visakh NR, who was rated 2507 before the game. I’ll also highlight a couple of critical moments leading up to these impulsive decisions.

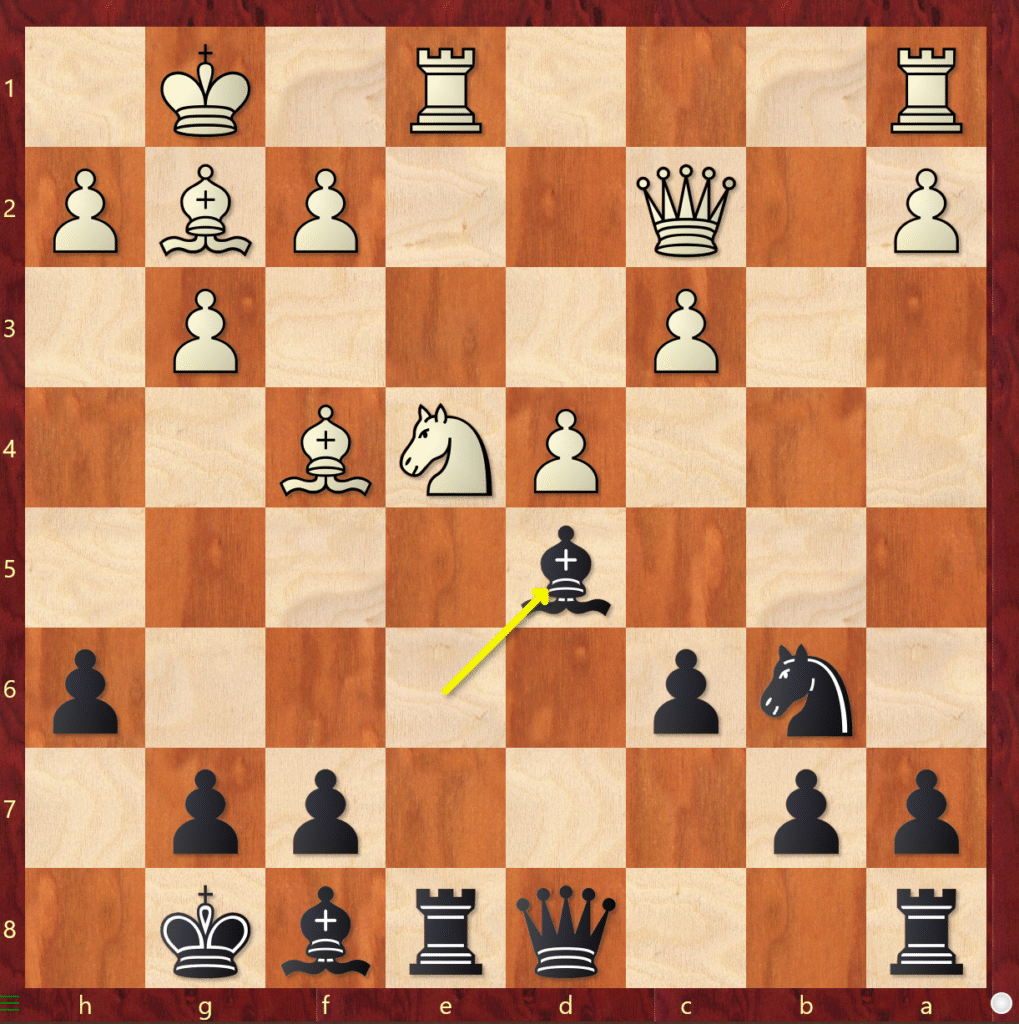

Let’s directly jump in after white’s 12th move. I missed my opponent’s 12.Ra1! move. Now 12….Bb2 is not great because of 13. Rb1 Bxc3 14. Rc1 and the c7 pawn falls. For some reason, I assumed Rb1 was forced, and I was planning to play Bf5 with a gain of tempo. This was the first critical position. Where do you think Black’s light-squared bishop belongs? White is also preparing to play Qb3 next—so what would you do about it?

I played 12…Bf5, probably the most logical move in the position. Then came 13.Qb3 Bd6 14.Bxd6 Qxd6 15.Nd2, and it finally became clear to me that White was pushing for an advantage. I realized I had made a slight inaccuracy. White is preparing to play e4 next, which seems to give him a symbolic edge. Moves like Ne4, Nc5, and so on are coming.

Let’s go back to the position after 12.Ra1. Here’s what I learned after analysing with the computer

- It’s better for black not to exchange the dark squared bishops. The reason being that once the dark squared bishops are exchanged, it’s easier for white to penetrate with e4 dxe4 Nxe4 and then Nc5. If black keeps the dark squared bishop then Nc5 is not a threat. Also d6 square will be controlled.

- Bishop on f5 is not very well placed if white is preparing to play e4. When playing 12…Bf5 I assumed that I should be able to stop e4 somehow but I don’t think it’s really possible. Then what’s the ideal square for light squared bishop? Suprisingly, it’s e6! The point is to prepare e4 break with dxe4 and then put the bishop on d5 to counter the g2 bishop! Once the center opens up with the bishop f5, the g2 bishop will become a pain.

Something like this would be a dream for Black! The bishop on d5 suppresses the g2 bishop, and it’s also worth noting that the dark-squared bishop keeps an eye on both the d6 and c5 squares.

Anyway, let’s move on. In the game, the following moves occurred: 12…Bf5 13.Qb3 Bd6 14.Bd6 Qd6 15.Nd2 Rfe8 16.Rfe1.

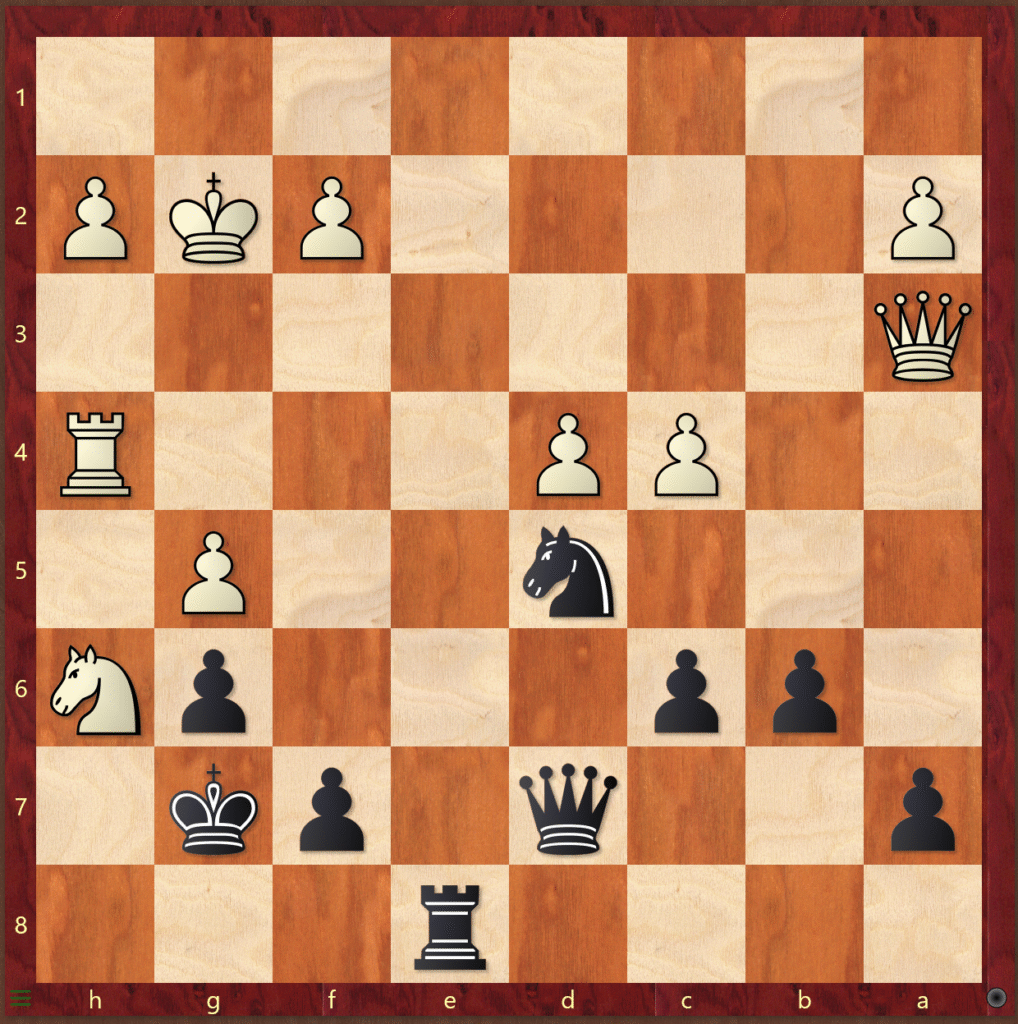

After a long think here, I realized that the bishop belonged on e6. So I played 16…Be6!? 17.e4!? dxe4 18.Ne4 Qd8 19.Qb5.

This was a semi-critical point. White had a very small positional initiative — he was planning to play Nc5, possibly a4 in some lines, and so on.

I wanted to play 19…Bd5 here and calculated this line a bit: 20.Nc5 Bg2 21.Kg2 Qd5 22.Kg1 Re1 23.Re1. I thought this should be within drawing range, but it still looked like something for White. A part of me didn’t want to liquidate the position and have to suffer for a draw — and another part of me did. These kinds of situations are psychologically tricky, especially when you’re not exactly sure what you’re fighting for.

Then I noticed I could play 19…c6!? If 20.Qg5, then I thought Qxg5 21.Qxg5 Bd5 was accurate, and I’d be completely fine. I briefly looked at 20.Qc5 and my thought process was: I can even go 20…Bd5 21.Nd6 Re1 22.Re1 Qd7, and I felt this should be okay since I’m going to exchange the light-squared bishops and simplify.

My opponent thought for a bit and played 20.Qc5 — and without much thought, I played out the whole line I had just described, like an idiot.

What did I miss here?

23.c4! — a simple move, after which I’m close to being busted. Honestly, I think it’s an easy move to spot. So why did I miss it? Because I didn’t think at all. I just played all my moves quickly after Qc5.

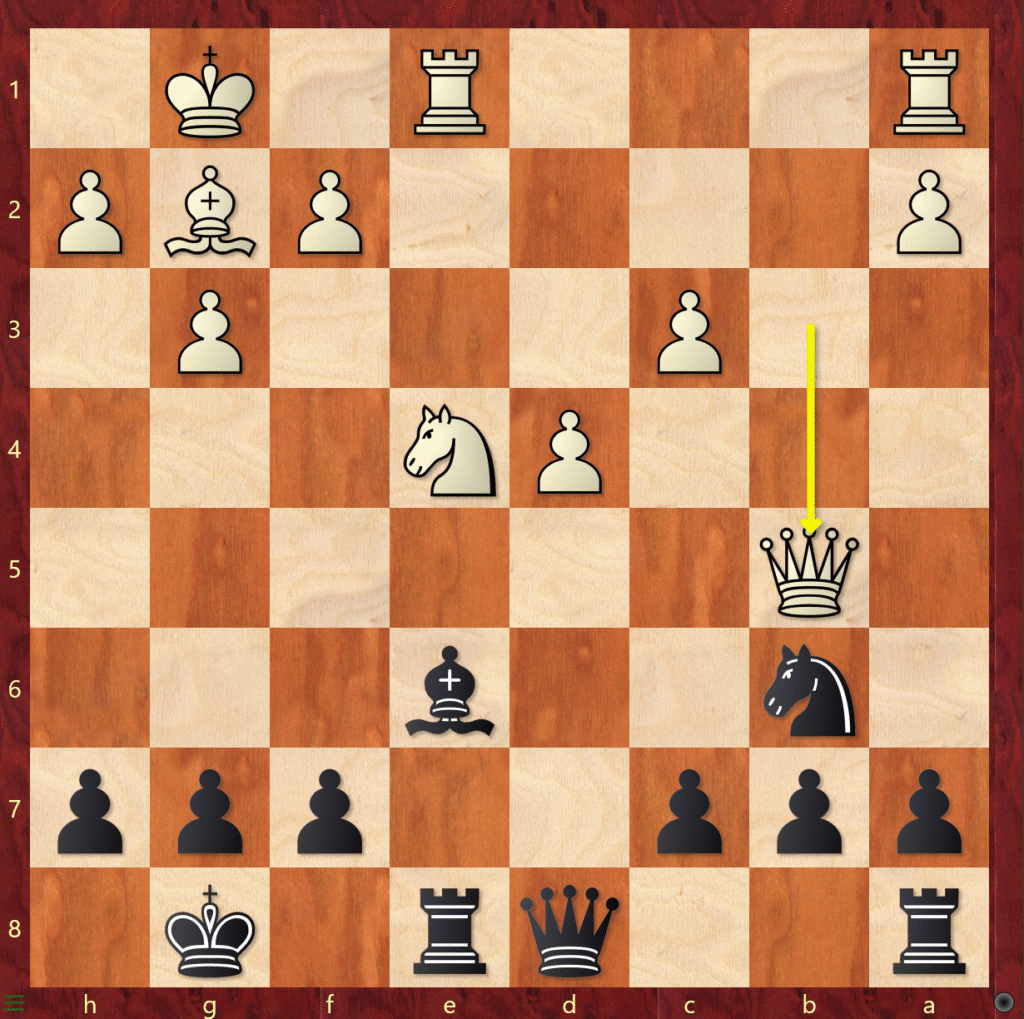

I even managed to make the position worse over the next few moves, and the following position arose.

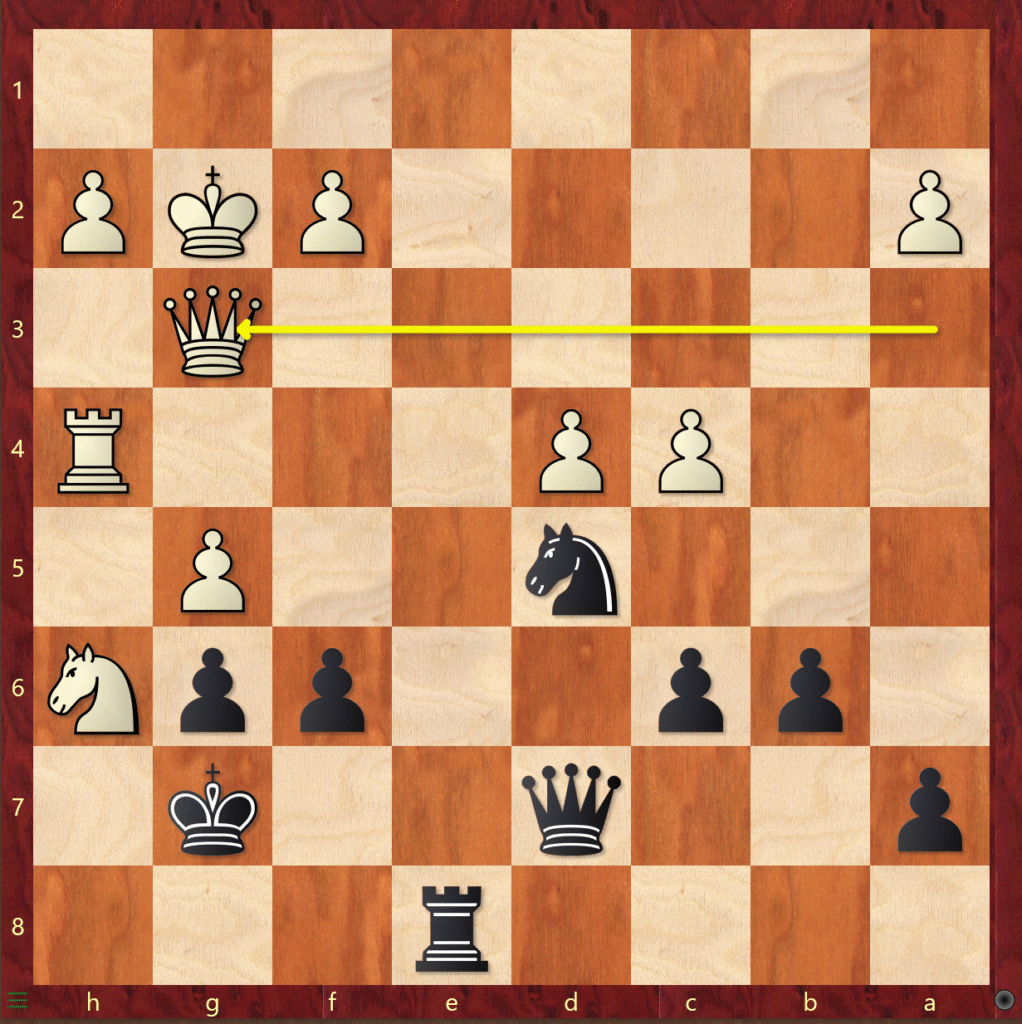

This is the position after 30.g5. White is clearly winning here, but I started to play well again. What is Black’s best try in this position?

30…Re8! — the idea being that if 31.Rxe8, then 31…Nf4, and 32.Kf3 is not possible due to 32…Qh3!.

White is still winning here — see if you can find how.

My opponent played 31.Rh4, which initially looked like the most critical try to me.

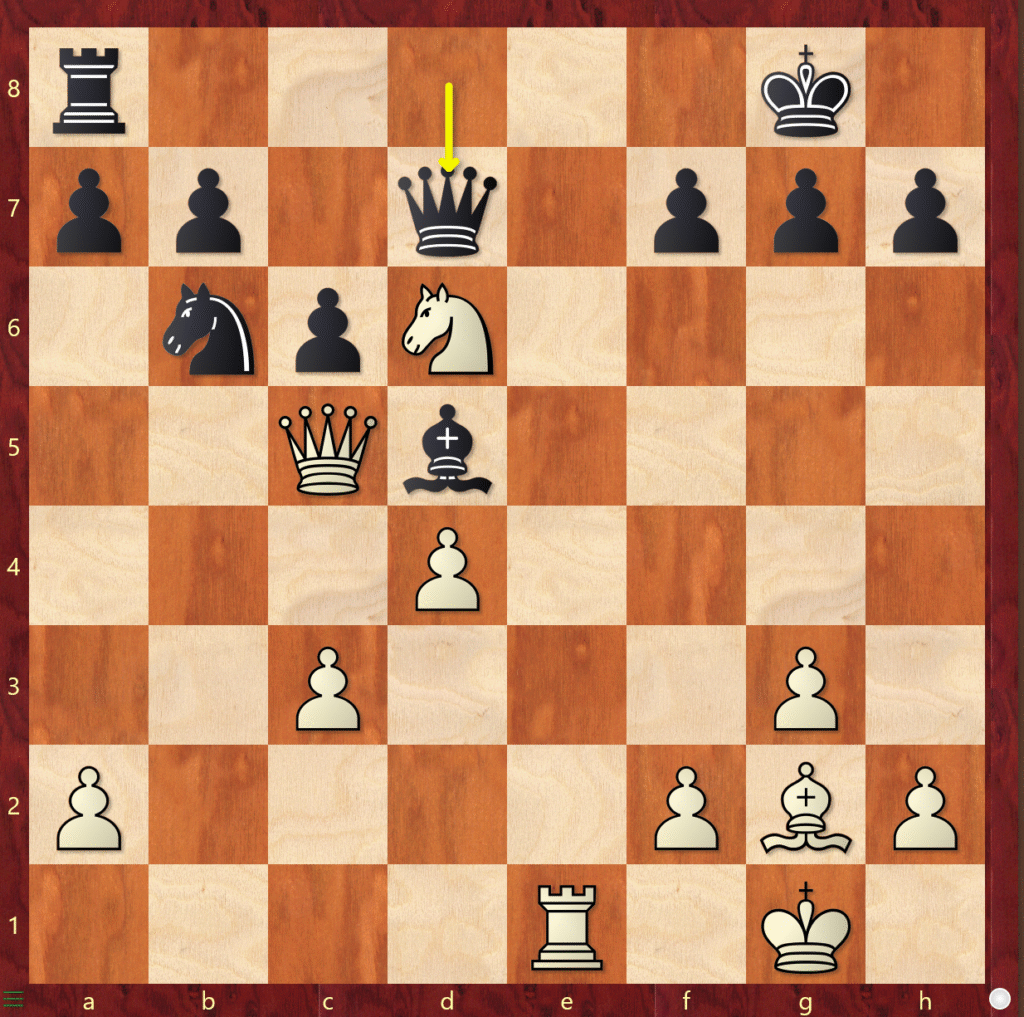

How should Black defend here? The next two moves I played — without any false modesty — were worthy of the best player in the world.

The correct move here is 31…f6! — the only move. The idea is that if 32.cxd5 fxg5! (32…Qd5 33.Kg3 followed by Ng4 wins for White), then 33.Rh3 Qd5. If 34.Qf3 Qxf3 35.Kxf3 Rh8, Black wins back the material. Even 34.f3 Re2 also seems quite okay for Black.

My opponent responded with 32.Qg3, which again is the most critical move in the position.

What would you play here as Black? Can you find the only move?

I played 32…b5!! — forcing White to make a decision about the c4 pawn. Here, I calculated a variation accurately to make it work: 33.cxd5 Qd5 34.Kh3. I considered this to be the critical line. Then 34…fxg5 35.Qc7+ Kf8 (it’s not mate, luckily), 36.Rg4 Re7!! — and I was proud of myself for seeing this.

The key point is that after 37.Qg3, there’s Rh7, and if 37.Qb8, then Kg7 — and Black is doing fine.

This was the main variation I was calculating while my opponent was thinking. I also briefly considered 33.gxf6 Nxf6 34.Ng4. I didn’t calculate it deeply, but I felt I could play 34…Ne4. If 35.Qh3, then Ng5!? stops Rh7. If 35.Qf4, then g5 — I thought — and I couldn’t believe it was actually working.

I was excited and went back to analyzing the other critical variation while my opponent was still thinking.

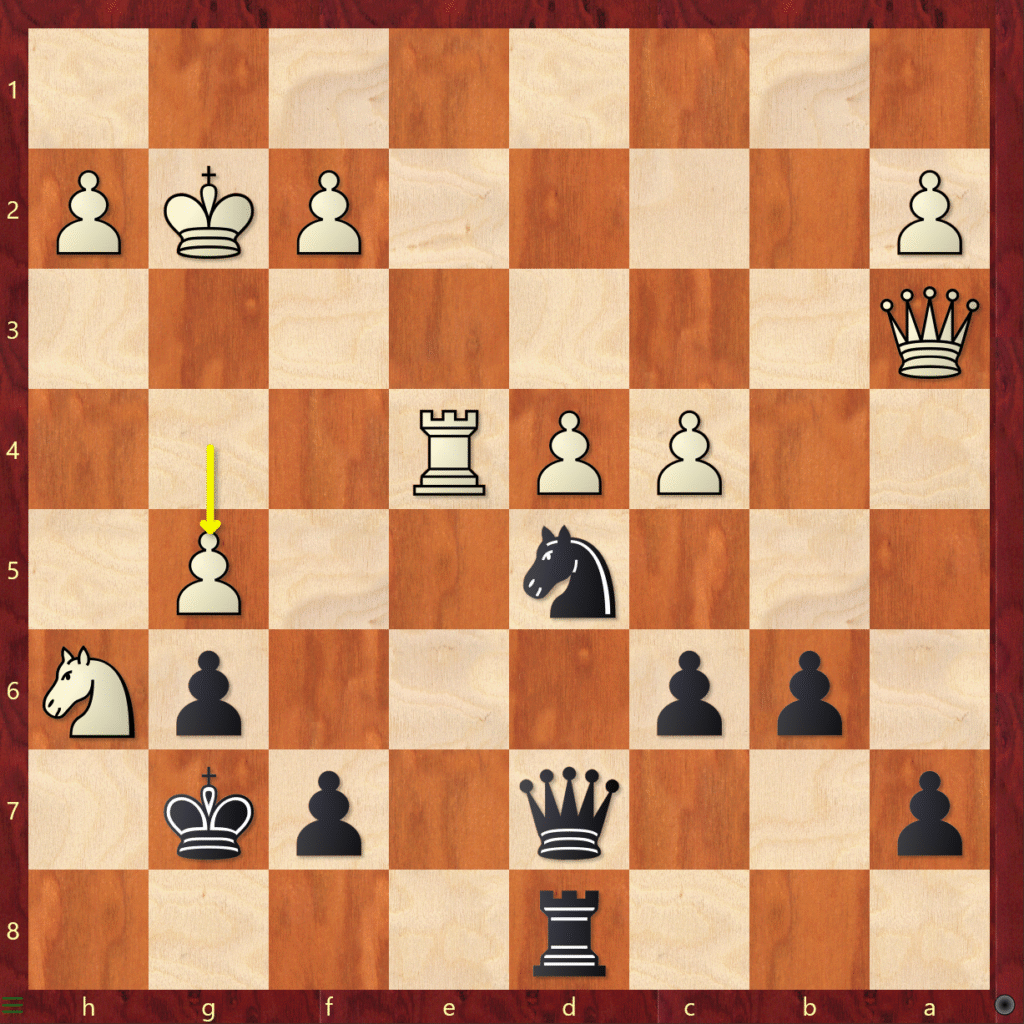

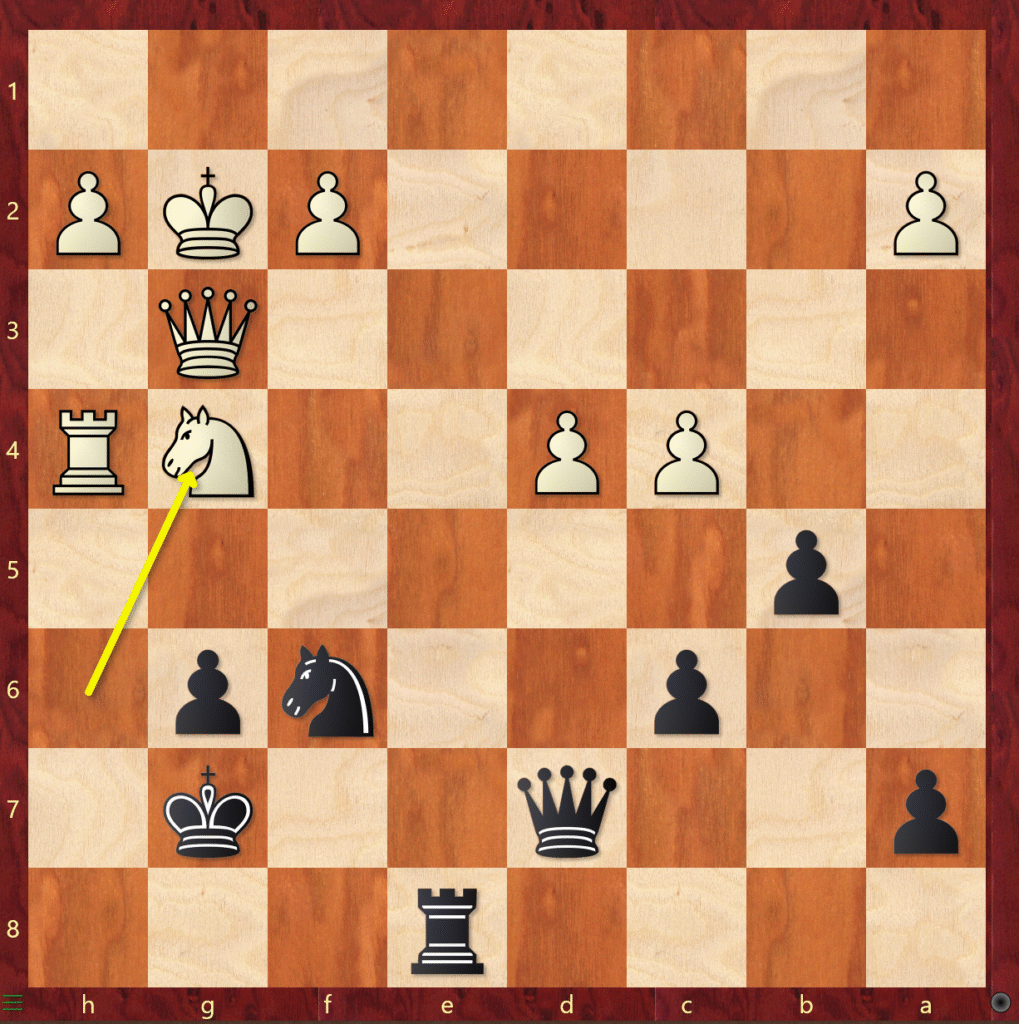

What happened next? My opponent played 33.gxf6 Nxf6 34.Ng4.

What do you think Black should play here? And what do you think I actually played?

Without a second thought, I played 34…Ne4. It loses rather easily after 35.Qe3. If g5 now, then 36.Ne5 follows. Funnily enough, 34…Ne4 35.Qh3 Ng5 is also a blunder because of Qc3 — and it loses too.

I still can’t understand how I could play moves like f6 and b5 in the previous two moves, and then suddenly play something like Ne4?! The equality was straightforward.

34…Nxg4 35.Rg4 Re6 is solid. The computer also likes 34…Qd4 35.Qc7 Nd4, though I’m not sure how practical that is over the board.

The main takeaway — for me and for you, if you’ve made it this far — is that playing too fast can be just as damaging as playing too slowly.

The reason I played 34…Ne4 so quickly was partly excitement and partly a desire to put pressure on my opponent, as we were nearing potential time trouble.

What frustrates me the most is this: even if I had spent just 10 seconds thinking about what White could do, I would have realized that my move was nonsense.

Here’s what I would do next time:

- I’ll avoid making impulsive moves or playing at blitz speed whenever it’s not necessary.

- If I still find myself tempted, I’ll force myself to spend an extra 30 seconds to a minute to check for flaws in my line.

- I’ll also take the time to consciously identify candidate moves, rather than locking in on one too quickly

Unfortunately, this was not the first time I have committed this mistake. Good or bad, I have a feeling I might end up repeating the same mistake. But recognizing it is the first step toward improvement. Chess is a constant learning process, and even our worst errors can teach us valuable lessons if we’re willing to reflect and adapt.

I hope sharing my experience helps you avoid similar pitfalls in your own games. Remember, patience and mindful thinking often make all the difference.

Useful links

How to deal with time pressure

Final Thoughts

Please excuse any inconsistencies in the chessboard sizes or formatting—I’m still learning the ins and outs of website design! My main focus is sharing my journey in chess improvement and the lessons I’ve learned along the way.

I’d love to hear your thoughts and feedback on this article. Whether it’s about the content, the analysis, or even the presentation, your input will help me grow as a player and a writer. Feel free to reach out to me directly at karthik@chess-cult.com

Thank you for reading, and here’s to improving together!

Leave a Reply